Locked Up Learning

Government statistical enquiry and academic research has consistently shown that the educational outcomes for children and young people in public care, including those in Secure Units, are seriously below national norms. The reasons include school and care placement breakdown, low expectations, a lack of understanding and effective communication between teachers and social care staff. Young people in the care system have lost considerable power in their lives: what power they have is often expressed in anger and violence. Young people in Secure Units are there as a result of Court Orders, where they are considered to be a danger to themselves or other people. In these circumstances the personal and social development of young people and their engagement with learning how to learn is a primary concern.

CLIENT BRIEF

The Leaders of the Secure Unit wanted to know:

Were there particular Learning Power characteristics of their young people that could help them design more targeted learning interventions?

Could Learning Power and Learning Journeys be a means of developing self-awareness, ownership and personal responsibility for these young people?

Could the language of Learning Power provide a bridge between social care and education?

HOW WE WENT ABOUT IT

We explored patterns in the Learning Power profiles of the entire cohort of 32 young offenders.

We supported the staff in co-designing and implementing personalised learning journeys for the young people, which began with self-understanding through Learning Power profiles and coaching conversations and led on to a personally chosen enquiry project for each youngster.

We captured qualitative and quantitative evidence of impact.

WHAT WE DID

Facilitated Learning Power coaching conversations with all of the young offenders, using popular media images from The Simpsons to communicate the meaning of the eight dimensions.

Stayed with them in these coaching conversations using their Learning Power to identify what they were uniquely interested in, until some authentic interest, sense making and curiosity emerged.

Guided them through an authentic enquiry cycle - starting with what they could observe and describe from their experience.

Introduced and coached them through learning to learn processes - generating questions, uncovering narratives, mapping knowledge.

Supported them in producing an outcome - a product - through which they demonstrated what they learned and how they had learned it.

Going into the ‘springboard zone’ with Bart Simpson to develop creativity! Coming up with new ideas, trusting your hunches, thinking around things…..

WHAT CHANGED

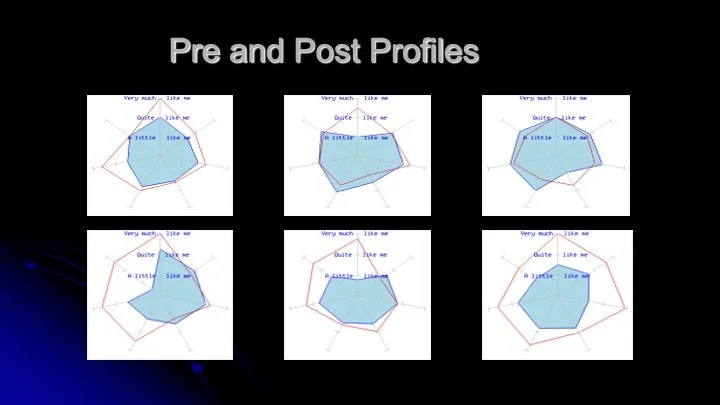

Most of the young offenders improved their Learning Power over the course of the project - as measured by their pre and post profiles and could tell a story of significant change.

Some Learners explained their own Learning Power profiles and the changes they had made as evidence in legal meetings.

Social Care team became involved in learning.

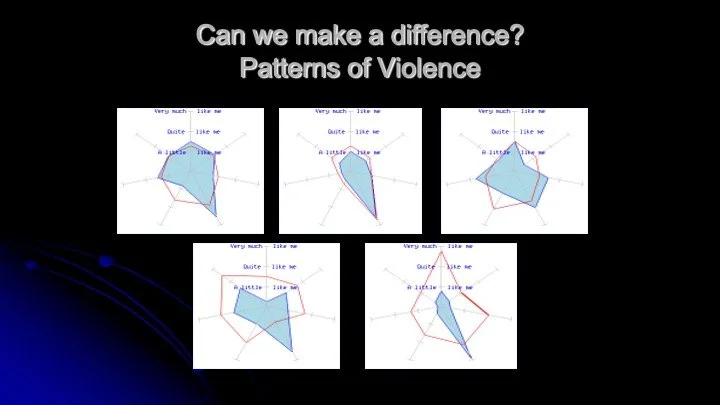

Patterns of Learning Power profiles emerged which demonstrated a relationship between low levels of seven of the Learning Power dimensions and extreme rigid persistence or extreme fragility and dependence (the eighth dimension).

Learning Power conversations opened up a different sort of learning conversation - one that began with the self-story of the learner and resulted in actions with measurable achievements.